Delivering the Impossible - Chapter 1

Version - 0.1 - Aristotle

Delivering the Impossible [Working Title]

Introduction

What was he doing? He was sniggering. He was actually sniggering. “So I see here that you’re writing a book - ‘Good Enough Project Management.’ How’s that going?”

I tried to explain how it was going - this was in an interview for a job with a big, big, exciting company as an Agile Coach. The answer of course was that it wasn’t going that well at all. I struggled to explain why I wanted to write a book that didn’t have a traditional, business book title like “Excellent Project Management”. I tried to explain I wanted to write a book about something not being totally perfect (think of the titles of some of the books written about software development - “Extreme Programming Explained”, “Clean Code”). What I wanted to write about was the realities of managing software development. A previous attempt at writing this book had been called “Late and Over Budget.” “You’re going to have to get a better title than that,” a friend told me.

Of course I didn’t get the job. How dare I suggest that project management should be “good enough” rather than “clean”, “perfect”, “pure” or “extreme”.

I’ve been wrestling with these ideas in one way or another since late 2011. Here’s what happened. I gave up my first real job as a Scrum Master on a big programme of development and got a job working at a start-up.

And in the first couple of weeks I managed to make the chairman of the start-up hang up the phone on me during a conference call. Why did he do that? I’d refused to promise that I would complete actions that I’d been assigned during the meeting.

The book that I wanted to write then came out of the realisation that the books that you read about project management such as “Agile Software Development with Scrum”, “Extreme Programming Explained” even the good ones like “Scrum and XP from the Trenches” gave the impression that if you followed the practises that were outlined in the books, your projects would be a success.

I couldn’t make the promise that the chairman wanted me to make because I knew from experience (the experience that they hired me for) that I might not be able to deliver. Real projects don’t run smoothly. They take longer than expected. They uncover the unexpected. They often end up costing far, far more than they’re expected to cost and deliver nowhere near the value that was promised. Whisper it, because although it’s obvious it’s treated like a dirty secret: software costs a fortune, and very often doesn’t deliver what’s expected of it.

I wanted to write a book that not only admitted these dirty secrets, but made project managers feel OK with what they were doing and what they were experiencing. And by project managers, I mean Scrum Masters, Delivery Managers, Product Owners, whoever it is who finds themselves on the hook for managing the delivery of a project and actually takes on that burden of responsibility for delivery.

But there are project managers and there are project managers. There’s a kind of project manager who hides what’s going on from the bosses using a variety of tactics: “project plans” that are hundreds-of-line-long; “reporting of progress” in terms of expenditure; hiding the bad news about the actual progress of a project for as long as possible; and acting surprised as senior stakeholders when deadlines are missed and there is no evidence that anything is produced. This is the kind of project manager who is happy to periodically enter a phase of “crunch”: late nights, weekend working and endless emergency meetings.

My book isn’t for those kind of project managers unless, they want to repent of their sins and actually do something to help the projects that they’re working on. Rather I’m writing for the kind of project manager who actually feels the need to take responsibility for the delivery of a project. I don’t care what their official title is. They might be project managers, they might, if they’re in publishing be called editors. They might be called directors. If they are on the hook for the delivery of a project and are trying neither to run-away from that nor deny it. If they’re worrying about it: those are the people this book is for. This book is aimed at the people who feel the responsibility for delivery. But it’s also a guide for those who try to help those people: agile coaches.

Why do I so want project managers and the people who support them to feel OK with what they’re doing and what they’re experiencing? Because I know it’s a painful, emotional business. I know because I’ve been through it a few times. And if there’s a way of making the whole business less painful; less filled with (negative) emotions and more successful! I think there should be a book that explains it. Right now, I don’t think there is. This is going to be that book.

So what is this book about? This book is about using the ideas of symmetry and asymmetry: “all” and “some”; “same” and “different” to explain some of the most common and upsetting problems in software development and to suggest some solutions to those problems. The book does this by explaining the sort of thing we are doing when we practice Agile or coach the practice of Agile. It explains how the power of an Agile approach is that it replaces implicit, unconscious “all”s with an explicit, conscious, “some”s and that this can be a very difficult thing to do, not only because the “all” (or “same”) that we are undermining has been arrived at unconsciously, but also because undermining these “all”s evokes considerable emotions, provokes defence and even provokes attack.

The inspiration for an analysis of Agile using these concepts of “All” versus “Some”; and “Same” versus different; is the work of Chilean psychoanalyst Ignacio Matte Blanco. I don’t think his work is very well known amongst the Agile or software development community, so Chapter 1 will be an introduction to some of the ideas in his work.

Chapter 1

An Introduction to the Work of Ignacio Matte Blanco

Ignacio Matte Blanco was a native of Chile who trained as a psychoanalyst in England in the 1930’s and then spent most of his professional career in Italy.

Asymmetric versus symmetric logic

Matte Blanco’s work is an intersection of psychoanalysis, particular the idea of thoughts being able to be both conscious and unconscious, with the structures of logical analysis. Matte Blanco’s central idea is that certain aspects of our thinking do not obey the laws of classical logic. An example of a law of classical logic - which Matte Blanco refers to a “asymmetrical” logic would be the law of contradiction.

In classical logic it is not possible for both X and ~X to be true.

Not (X and Not X)

Often classical logic is expressed as some statement about a class and its members. For instance so we can express the law of contradiction by saying that if something is a member of a class, it can’t also not be a member of a class.

Another principle of classical logic is that just because something is a member of two classes, does not mean that all the members of either class are members of the other class.

So if:

X is a member of class Y

It does not follow that Y is a member of class X.

For example - to use form that Socrates used to express his arguments, known as a syllogism:

Socrates is a human

It absolutely does not follow, in classical logic that:

All humans are Socrates

Matte Blanco’s contention is that sometimes classical asymmetric logic, which forbids contradiction and enforces the asymmetric nature of relations isn’t the kind of logic that we use. Rather, we use a form of logic which is symmetrical rather than asymmetrical. What does this mean? This means that in certain circumstances “some” is regarded logically as the same as “all”.

When this kind of logic is in operation then, from the point of view of classical logic, the world behaves very strangely.

Socrates is all humans

Romans are all humans

All Romans are Socrates

Even more disturbing than this, in symmetric logic, even the law of contradiction doesn’t hold. If we write the idea of X and not X out in the same way as we did the Socrates example.

X is true

X is not true

And applying symmetric logic then we get

All X'es are true

All X'es are not true

All X'es are both true and not true

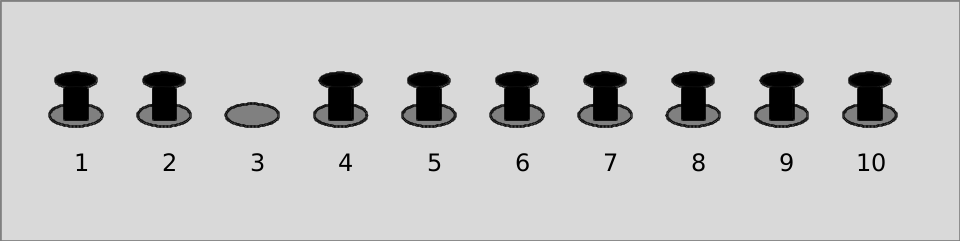

Matte Blanco has explanation of how, for the unconscious, and sometimes for the conscious mind, it is extremely difficult to understand that something does not exist. The example he gives is if you have a one-dimensional series, let’s say that you have a series of slots in a row, and the slots are numbers with the integers. And that there is a peg indicating true in each peg 1-10 except the 3 peg. Matte Blanco’s point is that there is still a hole for the peg - and a number next to it. There is a structure - the one-dimensional array of pegs that, yes, shows that there’s no peg in the number 3 slot. But is doesn’t actually pick out the full logical meaning of “not 3”. The full logical meaning of “not 3” is “anything but 3” this includes all the numbers in this series except 3 but it also includes anything else that is thinkable - along any other dimensions, not included within this particular series.

Another important implication of symmetrical logic is that where symmetrical logic is being used temporal relations are impossible. Temporal relations can only happen if relations can be asymmetric e.g. x is before y. P is in the future, Q is happening now, R is in the past. This means that in symmetrical logic, from the point of view of time, everything is not only now, but always has been and always will be.

What Does Any of This Have to Do with Software Development or Project Management?

Why am I talking about this in a book about project management, especially the project management of software development? Because symmetrical thinking is present in multiple forms throughout the software development process, and the best way we know of doing software development - Agile - works by, easing, challenging and at some points directly attacking symmetrical thinking.

Here are some of the ways that symmetrical thinking is present in software development.

All

Before the advent of Agile approaches to software development there was waterfall. Idea of a waterfall approach was that the way to deliver a successful project was to write down in a requirements document absolutely all the requirements for the project. When that was done (let’s not worry too much right now how we’d know when it was done), that document would be used to create a complete system design. And when that was done (never mind about how we’d know when it was done), development would start. When development was finished, testing would start, and then when testing was finished, in theory, user acceptance testing would start.

That was the theory, but usually, at some point during either development (which would take far, far, too long - much longer than “estimated”), or during testing (which would reveal either that the system didn’t do what the customer asked for in the requirements, or, more likely that the system did do what was in the requirements, which it was now obvious to the customers, wasn’t what they now wanted) there would be a crisis.

Writing about it now, in the 21st century, it seems impossible to believe that this would be a reasonable approach to developing software. Indeed, it does sound impossible if it weren’t for the fact that at least on two occasions in the last six months it’s been suggested to me that this approach would work better than an Agile approach, or that we should revert to a waterfall approach because an Agile approach isn’t working.

Why is such an approach so appealing? I think a substantial part of the reason is the powerful appeal of “all”.

Same

“Real life Fagin ran gang of pickpockets from Hackney flat”

“Real life ‘Pretty Woman’ married her millionaire client in fairy tale ceremony”

Every now and then there is a story in the news of something that has happened in real life that is sort of like something that happened in a novel or a film. If we stop for just a second, we might ask why? Why would this be news? And lots of things happen in the world. The two described above, although unusual aren’t that unusual. Why should it be of interest to anyone that these turns of events match on a very superficial level? One answer is that, similar to the power of “all”, in its persuasive and attractive power of “same.”

These stories are interesting, and somehow rewarding because they show similarities between the world of imagination and the world of reality. In the world of waterfall projects, one powerful idea of success of a project was a project that was delivered exactly what was in the specification, exactly on time and exactly to budget: same specification, same duration and same cost equals success. Doesn’t it?

Same is very powerful in several other ways. Same is especially powerful when projects get started. How many iPhone apps, or Facebook apps were created with an argument of the form “everyone else is getting an app”. As noted by Robert Cialdini in his book “Influence”, “We view a behaviour as more correct in a given situation to the degree that we see others performing it.”

Always, Now and Forever

The past comes before present, the present comes before the past. Time isn’t symmetrical, it is fundamentally asymmetrical. So it’s not surprising that symmetrical thinking about time is very strange.

The Absence of Negation

As described above in the example of the “Number 3” in the peg board. The negation of specific idea makes that idea very real in a way that is very different from the actual logical implications of something not existing. “Not Number 3” logically means “anything but an elephant”.