Review: John Boyd and the OODA loop

John Boyd - The OODA Loop and the Buttonhook Turn:

What can Military Strategy Teach us About Project Management?

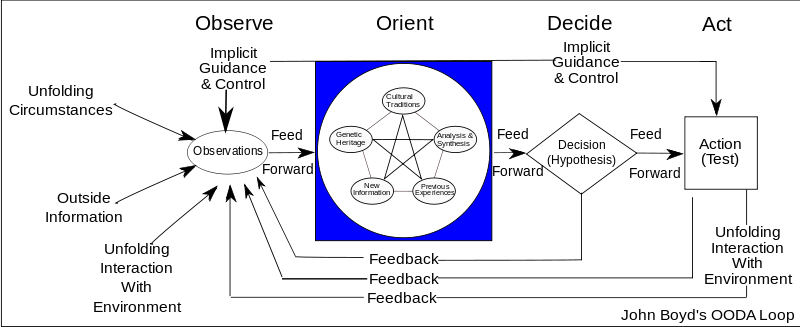

So, enough about improv for the moment (although, I’m sure we’ll be back to it very soon). I’ve been reading this book: “Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War” for the last week or so. It takes a while to get to the point - so I might just start with it. The point is that succeeding in war isn’t about speed, it’s about manoeuvrability - agility even, it’s about being able to get through something called the “OODA loop” (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) faster than your opponents.

I’ve always been a little bit nervous using military analogies when talking about project management. Because, for me, software development is a quite business that involves talking, thinking and typing and talking about it in military terms conjures up images of groups of dressed-by-their-mother Nietzschean “supermen” pretending that typing in Java class definitions is something like fighting a war. But then again, one of the interesting things about this book is that the “real” wars are a merely a backdrop to the organisational conflicts inside the US Air Force, US Marines and the Pentagon that Body spent most of his life fighting. War may be something that happens a long way off that I don’t want to look foolish by presuming to know much about - but conflict? That’s everywhere.

Anyway, here’s the Boyd story as told by this book:

1. Fighter Pilot - “40 Second Boyd”

This guy Boyd was a really good fighter pilot, not so much in a “real” war - although he did fly at the tail end of the Korean War, but as a fighter pilot instructor. As a fighter pilot instructor, he developed a manoeuvre that meant that he could essentially stop suddenly in mid-air and force whoever was pursuing him to overtake him, he could then drop back onto their “six” (immediately behind them) and “hose” them (shoot them down). In a training dogfight, he could apparently do this within 40 seconds.

2. That’s Entropy Man

My knowledge of thermodynamics comes from Flanders and Swann (my dad’s eclectic selection of go-to-sleep records rears its head again). After his success as a fighter pilot trainer, Boyd decided he needed to do a college degree and so he did a degree in Engineering at Georgia Tech. As part of that degree he learned about Thermodynamics, the ideas of energy conservation and also, the idea of “times arrow” that in any closed system, the amount of disorder will always increase.

Rather unsurprisingly, Boyd applied these ideas to fighter planes. He realised that you could use thermodynamics equations to express the manoeuvrability of fighter planes. He also realised that by looking at fighter planes through the lens of thermodynamic equations it was possible to focus on the properties that fighter planes really needed in order to be successful. What’s important in fighter planes isn’t so much that they can go fast, it’s that they can “pump and dump” - they can gain energy fast (speed up), they can lose energy fast (slow down) and they can convert it (from potential energy - being higher in the sky - to kinetic - moving fast - to potential again). Having developed equations to express this idea it was also then possible to compare fighters with the “enemies” fighters and with other competing designs, and really start causing trouble.

3. “I could fuck up and do better than this”

Using these equations Boyd started to produce diagrams that showed where US fighter planes outperformed Russian and other fighter planes, and where they didn’t. One of the most controversial findings of this approach was that there was nowhere in the set of possible manoeuvres where the F111 out-performed the competition. In short, it was a dud. As Boyd said to a General in the Air Force in a presentation “I could fuck up and do better than this.” This realisation was the start of a long battle inside the Pentagon for Boyd and his acolytes to make sure that the planes that followed the F111 weren’t such death traps for the pilots that flew them. Ultimately this resulted in major changes to the F15 and the design of a “super lightweight” fighter as the result of trials between prototypes - the F16 (the Navy took the loser in the trials and called in the F17).

Aside number 1: Reading about the F111 is spookily like reading about every big IT project that you’ve ever worked on. It had too many features and each additional feature added more than its own complexity to the complexity of the overall project. It featured a huge design compromise - the swing wing - which allowed it to be both a fighter and a bomber. Again this compromised to make it “multi-function” made it disproportionately heavier and and more complex and ultimately made it less likely to fulfill any of the jobs it was supposed to do.

4. Button Hook Turns

Early trials of the F16 (before the dark forces in the Pentagon got at it and covered it with extra weapons systems and mountings for missiles to make it “multi-purpose” and therefore slower and more likely to kill its occupant) resulted in reports from test pilots of amazing manoeuvrability - they talked of being able to do “button hook turns” - being able to rapidly turn back in on themselves - crucially within the turning circle of the enemy. This was Boyd’s theories of thermodynamics in action - but it also got him thinking metaphorically along the lines of being able to “turn within the enemy’s circle.”

Boyd had also been thinking about why the F86 which was flown in the Korean war had done as well as it had relative to the Russian Mig fighters that they were up against. According to Boyd’s theories - the Mig’s should have won. He realised that there were other ways in which the F86 was superior - it had 360 degree visibility, which the Mig didn’t have and it had purely hydraulic controls against the Mig’s manual controls (which apparently required the pilots to do weight-training to operate).

Aside 2: These two benefits have analogues in project management, seeing where you are is obviously a massive advantage. This is David Anderson’s “visualise the work.” But the hydraulic controls have an analogue in project management as well. When you make decisions about actions (see the next section) you want fast feedback from your team. And that is probably going to mean that they’re in the same country, probably the same room. I’m not saying it’s impossible to get that kind of “hydraulic” response with distributed, offshore teams, but it’s a lot harder. So much of the time when you’re working with offshore teams you feel the need to do weight training.

5. Reading the Wrong Thing and the OODA Loop

Boyd then did something that is very dear to my heart. He read all over the place. And as he went on this journey, he talked in a series of military briefings that he gave in the pentagon and in various branches of the military. Out of this came a bunch of ideas that I’m still trying to understand and his notion of the “OODA loop”.

There are a couple of things that I really like about the “OODA Loop”.

- it’s a loop, it’s a fundamentally iterative idea.

- it isn’t a loop, it’s a far more complex graph, with feedback lines all over the place. I like the fact that it captures the idea that feedback happens all the way through any project and needs to be responded to, sometimes by backing up - from orientation to observation for example.

- thinking in terms of the OODA loop with the knowledge of its heritage in thermodynamics allows you to think of it terms, not of speed, but of manoeuvrability. What’s important in what are sometimes called VUCA environments (Volatile, Uncertain, Chaotic and Ambiguous) is not how fast you can go, but how fast you can change direction in response to the circumstances and learning. If you can bring the tempo of your learning loop inside that of your competitors, you will win.

- Finally, it makes me see a fundamental flaw in talking about either Minimum Marketable Feature or Minimum Viable Product. The OODA loop is about harvesting experience, it’s about learning in the VUCA environment. Experience is what you get when you don’t get what you want (“what you want” = value), but experience is necessarily what you have to collect on the way to what you want. There’s a real danger when talking about Minimum Marketable Features and Minimum Viable Products that the initial OODA loop will get huge because anything smaller won’t deliver value. Some questions that I want to answer using “OODA loop” forays in any project which don’t actually directly deliver any business value but deliver huge amounts of understanding.

- To what degree is this business capable of articulating its requirements?

- To what degree are the analysts on this team capable of capturing them?

- To what degree are the developers capable of instantiating them?

- To what degree are the testers capable of testing them?

- Is the architectural solution fit-for-purpose?

- Can the hardware actually be put in place?

- Is the organisation capable of governing the project without killing it with process?