Delivering the Impossible - Chapter 2

Version - 0.1 - Aristotle

Delivering the Impossible [Working title]

Chapter 2

What is Agile?

One of the strange things about social media is that sometimes talk about work and talk with friends gets mixed up. As a result, friends of mine who know nothing of software development get to see me ranting about Agile or SAFE or someone behaving badly in a stand-up. Occasionally they mention to me that they have no idea what I’m talking about.

And some of these friends have actually started to read this book. As one put it “I read all the way through to the elephant.” And I’m wondering if it’s possible to keep those people reading through what has to be the next chapter of the book. This is a chapter which explains why these observations about “some” and “all” should be of interest to anyone who’s involved in managing projects, but especially software development projects.

To explain this, we need to talk about the Agile manifesto, and how it encourages a “some” approach to thinking about software development and then we need to talk about the most successful Agile method: Scrum.

But in order to explain what the Agile manifesto is, we need to explain what Agile is. And in order to explain what Agile is? Well, really to explain what Agile is, we need to explain what Agile isn’t and how we used to do things before Agile. Fortunately, all of this backing up to get a better run at things is totally relevant to the central idea of this book: that things go wrong when you use “all” where you should use “some” and things get better when you use “some” instead of all.

What is Waterfall?

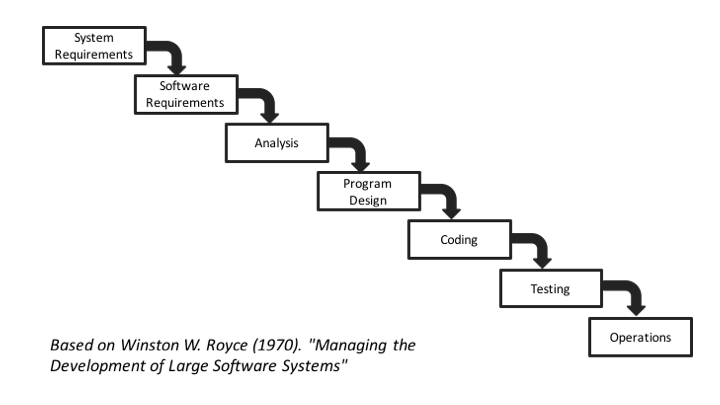

Until the end of the 21st century it was widely thought that the best way to manage software development was to treat it like the engineering of complex physical structures, like engines or suspension bridges. This type of approach is often called a “Waterfall” approach because of the way that’s represented in diagrammatic form.

When a piece of software was required, it was understood that the best way to make sure that that piece of software was delivered “on time” and “to budget” was to make a list of absolutely everything (all of the things) that the piece of software needed to do in a “requirements document”. When that document was complete, and only when it was complete, another document would be written which explained exactly how those requirements would be satisfied. This would probably be called a “design document.”

Eventually, when the design was complete, some software developers could start to write some software.

When the developers had finished doing this, everything that they had written would be passed on to testers who would test what the developers had done against the initial requirements document. When they had confirmed that the software did everything that was outlined in the initial requirements document, the software would be handed to the customers to do their own testing, sometimes called “factory gate” testing, sometimes called “acceptance testing”. When the customers had convinced themselves that the software did exactly what they’d asked for in the requirements document, the software would be released and put live. And everybody would live happily every after. At least that was the theory.

What’s Good About Waterfall?

One of the things that’s good about the waterfall approach is its universal, intuitive appeal. Given the discussions that we had in the introduction and Chapter 1, it might be possible to see why.

The idea of doing all of something has tremendous appeal.

When you’re tackling a big, complicated project, making a list of everything (all the things) that you want the project to do seems like a good idea. It seems like the safest way of making sure that you don’t miss anything, that you get all the things that you want.

The other good thing about waterfall approaches to projects is directly related to this powerful, intuitive appeal. Put very simply, senior management like the sound of “all”. “All” sounds complete. “Some” sounds messy. Lots of projects like this got funded. And as the architectural writer Stuart Brand points out: “Form follows funding.”

What’s Bad About Waterfall?

So what’s wrong with waterfall? When I started in software development, “waterfall” project management wasn’t called “waterfall”:it was just called “project management”. It was simply the only kind of project management that there was.

The first two projects (an accounting system for an oil company and a weapons simulation system) that I worked on had been through extensive requirements gathering phases. They’d then been through complex design phases, and then, after a long, long time, software development had started. Both were multi-million pound development projects. And after the requirements, design, development and testing phases, both projects had had an unexpected, additional phase: litigation. Yes, that’s right. On both projects, the clienti had threatened to sue us as suppliers because they were so unhappy with the way that the work was going.

What brought on these crises? Several things. First of all, getting to the point where the customers could see working software had taken far, far, longer than had been initially estimated. This caused all kinds of our problems for our customers who were betting on the systems being available so they could build service stations, train personnel, start wars.

Secondly, when they customers did get to see the software, it wasn’t what they were expecting.The realisation that the software was not only late, but also the wrong thing caused a crisis in the clients so profound that they wanted us as suppliers to really smart. Blame, shame, wounding costs and reparations needed to be handed off onto the people who’d committed this abomination and so the lawyers were called.

Finally, by the time our customers got to see the software the world had changed. New territories with new requirements had opened up for the oil. Wars in different parts of the world looked like opportunities for the arms manufacturers. While we’d been beavering away writing the requirements, coming up with the design, writing the software and then finally testing it, the world had changed. A substantial part of why the customers didn’t want to pay for software we showed them, and so had called in the lawyers, is that even it was exactly what they’d asked for in the requirements document, it wasn’t what they wanted anymore.

But here’s an interesting thing. Both projects, when I worked on them were making money for the company. Both projects were also delivering software to the customers. In both cases the company had called in a negotiator who specialised in helping out projects that had reached this crisis phases. He was a tiny Glaswegian (I’m 5’ 5” and he was a good head shorter than me) called Terry.

Terry would negotiate with the clients; he would tolerate the their shouting and cursing and recriminations with good grace; he would find out which bit of the software the clients desperately needed most and he would agree to deliver that in a short space of time, say a month or so.

But part of that agreement would be getting the client to agree to drop the threats of the law suit and pay a little bit more money. Slowly but surely, the client would start to get a system that they could use and were happy with, if still not ecstatic. Slowly but surely they would forget the threat of legal action and concentrate on identifying what the next thing was that they wanted us to work on.

I didn’t really understand it then, but to me now, it’s obvious what Terry was doing. In the midst of customer wailing, gnashing of teeth and threats of legal action, Terry was negotiating the replacement of “All” with “Some”. Rather than promising “All” of the project, he was agreeing to supply “Some”. And this became much easier at the point where the client was really seriously looking at the possibility of ending up with nothing but a long and drawn-out law suit. Focusing on some rather than all also provided an opportunity to incorporate any changes that the customer wanted that weren’t in the original specification.

The Need for “Lightweight” Methods

Terry was, in this aspect a bit ahead of his time. But not that far ahead. By the mid-nineteen-nineties, several forces were combining in the world of software to make this kind of approach more principled and explicit. For one thing computers were getting all GUI - that’s an acronym for Graphical User Interface. Firstly widely available with the Apple MacIntosh, but then far more widely spread with Windows 95, users were wanting to point and click at things in windows and buttons and menus rather than type special commands into computer that had a very old-fashioned looking green screen.

And it turned out that GUI’s were really, really hard to specify in requirements documents. They were much better served by a process that “iterated” through a series of “prototypes.” That is, you start off with a rough sketch of what you want the GUI to look like and show it to the people who want it - maybe even give them a chance to try it out, you take their comments into consideration: “Where the hell’s the undo button?” “I thought this would be purple!” and then you produce another version. Each of those version is a new prototype. Each journey around the loop, getting feedback, making modifications and then producing a new version is an iteration.

Mean while, in the USA, a change was being negotiated to the rules governing the use of an obscure computer network used by academics and military personnel and nerds. The rule change would allow the network to be used by commercial enterprises. And in Switzerland a researcher at the European Centre for Nuclear Research was making his idea for how to get access to documents on other people’s computers free to anyone who cared to use it. The internet and the worldwide web were about to meet and start to have children. Commentators were about to start using the phrase “internet speeds” to talk about the ferocious pace of change. And all of a sudden, nobody wanted to wait eighteen months to find out their software wasn’t what they expected and call their lawyers.

Still, it took a while: throughout the 90’s and into the 00’, various attempts were made to codify this new iterative, prototyping approach. These new methods, Rapid Application Development, Extreme Programming came to be generally referred to as “lightweight” methodologies. Although few people were happy with that as a label.

So in 2003 a bunch of these men who were interested in these “lightweight” methodologies (they were ALL men) got together in a ski lodge hotel in Utah to discuss a better way of presenting what they were doing. The result of that meeting was a 93 word statement known as the Agile manifesto.