Book - Delivering the Impossible

Version - 0.1 - Aristotle

Delivering the Impossible

Introduction

What was he doing? He was sniggering. He was actually sniggering. “So I see here that you’re writing a book - ‘Good Enough Project Management.’ How’s that going?”

I tried to explain how it was going - this was in an interview for a job with a big, big, exciting company as an Agile Coach. The answer of course was that it wasn’t going that well at all. I struggled to explain why I wanted to write a book that didn’t have a traditional, business book title like “Excellent Project Management”. I tried to explain I wanted to write a book about something not being totally perfect (think of the titles of some of the books written about software development - “Extreme Programming Explained”, “Clean Code”). What I wanted to write about was the realities of managing software development. A previous attempt at writing this book had been called “Late and Over Budget.” “You’re going to have to get a better title than that,” a friend told me.

Of course I didn’t get the job. How dare I suggest that project management should be “good enough” rather than “clean”, “perfect”, “pure” or “extreme”.

I’ve been wrestling with these ideas in one way or another since late 2011. Here’s what happened. I gave up my first real job as a Scrum Master on a big programme of development and got a job working at a start-up.

And in the first couple of weeks I managed to make the chairman of the start-up hang up the phone on me during a conference call. Why did he do that? I’d refused to promise that I would complete actions that I’d been assigned during the meeting.

The book that I wanted to write then came out of the realisation that the books that you read about project management such as “Agile Software Development with Scrum”, “Extreme Programming Explained” even the good ones like “Scrum and XP from the Trenches” gave the impression that if you followed the practises that were outlined in the books, your projects would be a success.

I couldn’t make the promise that the chairman wanted me to make because I knew from experience (the experience that they hired me for) that I might not be able to deliver. Real projects don’t run smoothly. They take longer than expected. They uncover the unexpected. They often end up costing far, far more than they’re expected to cost and deliver nowhere near the value that was promised. Whisper it, because although it’s obvious it’s treated like a dirty secret: software costs a fortune, and very often doesn’t deliver what’s expected of it.

I wanted to write a book that not only admitted these dirty secrets, but made project managers feel OK with what they were doing and what they were experiencing. And by project managers, I mean Scrum Masters, Delivery Managers, Product Owners, whoever it is who finds themselves on the hook for managing the delivery of a project and actually takes on that burden of responsibility for delivery.

But there are project managers and there are project managers. There’s a kind of project manager who hides what’s going on from the bosses using a variety of tactics: “project plans” that are hundreds-of-line-long; “reporting of progress” in terms of expenditure; hiding the bad news about the actual progress of a project for as long as possible; and acting surprised as senior stakeholders when deadlines are missed and there is no evidence that anything is produced. This is the kind of project manager who is happy to periodically enter a phase of “crunch”: late nights, weekend working and endless emergency meetings.

y book isn’t for those kind of project managers unless, they want to repent of their sins and actually do something to help the projects that they’re working on. Rather I’m writing for the kind of project manager who actually feels the need to take responsibility for the delivery of a project. I don’t care what their official title is. They might be project managers, they might, if they’re in publishing be called editors. They might be called directors. If they are on the hook for the delivery of a project and are trying neither to run-away from that nor deny it. If they’re worrying about it: those are the people this book is for. This book is aimed at the people who feel the responsibility for delivery. But it’s also a guide for those who try to help those people: agile coaches.

Why do I so want project managers and the people who support them to feel OK with what they’re doing and what they’re experiencing? Because I know it’s a painful, emotional business. I know because I’ve been through it a few times. And if there’s a way of making the whole business less painful; less filled with (negative) emotions and more successful! I think there should be a book that explains it. Right now, I don’t think there is. This is going to be that book.

So what is this book about? This book is about using the ideas of symmetry and asymmetry: “all” and “some”; “same” and “different” to explain some of the most common and upsetting problems in software development and to suggest some solutions to those problems. The book does this by explaining the sort of thing we are doing when we practice Agile or coach the practice of Agile. It explains how the power of an Agile approach is that it replaces implicit, unconscious “all”s with an explicit, conscious, “some”s and that this can be a very difficult thing to do, not only because the “all” (or “same”) that we are undermining has been arrived at unconsciously, but also because undermining these “all”s evokes considerable emotions, provokes defence and even provokes attack.

The inspiration for an analysis of Agile using these concepts of “All” versus “Some”; and “Same” versus different; is the work of Chilean psychoanalyst Ignacio Matte Blanco. I don’t think his work is very well known amongst the Agile or software development community, so Chapter 1 will be an introduction to some of the ideas in his work.

#Chapter 1 #An Introduction to the Work of Ignacio Matte Blanco Ignacio Matte Blanco was a native of Chile who trained as a psychoanalyst in England in the 1930’s and then spent most of his professional career in Italy.

##Asymmetric versus symmetric logic

atte Blanco’s work is an intersection of psychoanalysis, particular the idea of thoughts being able to be both conscious and unconscious, with the structures of logical analysis. Matte Blanco’s central idea is that certain aspects of our thinking do not obey the laws of classical logic. An example of a law of classical logic - which Matte Blanco refers to a “asymmetrical” logic would be the law of contradiction.

In classical logic it is not possible for both X and ~X to be true.

Not (X and Not X)

Often classical logic is expressed as some statement about a class and its members. For instance so we can express the law of contradiction by saying that if something is a member of a class, it can’t also not be a member of a class.

Another principle of classical logic is that just because something is a member of two classes, does not mean that all the members of either class are members of the other class.

So if:

X is a member of class Y

It does not follow that Y is a member of class X.

For example - to use form that Socrates used to express his arguments, known as a syllogism:

Socrates is a human

It absolutely does not follow, in classical logic that:

All humans are Socrates

atte Blanco’s contention is that sometimes classical asymmetric logic, which forbids contradiction and enforces the asymmetric nature of relations isn’t the kind of logic that we use. Rather, we use a form of logic which is symmetrical rather than asymmetrical. What does this mean? This means that in certain circumstances “some” is regarded logically as the same as “all”.

When this kind of logic is in operation then, from the point of view of classical logic, the world behaves very strangely.

Socrates is all humans

Romans are all humans

All Romans are Socrates

Even more disturbing than this, in symmetric logic, even the law of contradiction doesn’t hold. If we write the idea of X and not X out in the same way as we did the Socrates example.

X is true

X is not true

And applying symmetric logic then we get

All X'es are true

All X'es are not true

All X'es are both true and not true

atte Blanco has explanation of how, for the unconscious, and sometimes for the conscious mind, it is extremely difficult to understand that something does not exist. The example he gives is if you have a one-dimensional series, let’s say that you have a series of slots in a row, and the slots are numbers with the integers. And that there is a peg indicating true in each peg 1-10 except the 3 peg. Matte Blanco’s point is that there is still a hole for the peg - and a number next to it. There is a structure - the one-dimensional array of pegs that, yes, shows that there’s no peg in the number 3 slot. But is doesn’t actually pick out the full logical meaning of “not 3”. The full logical meaning of “not 3” is “anything but 3” this includes all the numbers in this series except 3 but it also includes anything else that is thinkable - along any other dimensions, not included within this particular series.

Another important implication of symmetrical logic is that where symmetrical logic is being used temporal relations are impossible. Temporal relations can only happen if relations can be asymmetric e.g. x is before y. P is in the future, Q is happening now, R is in the past. This means that in symmetrical logic, from the point of view of time, everything is not only now, but always has been and always will be.

What Does Any of This Have to Do with Software Development or Project Management?

Why am I talking about this in a book about project management, especially the project management of software development? Because symmetrical thinking is present in multiple forms throughout the software development process, and the best way we know of doing software development - Agile - works by, easing, challenging and at some points directly attacking symmetrical thinking.

Here are some of the ways that symmetrical thinking is present in software development.

All

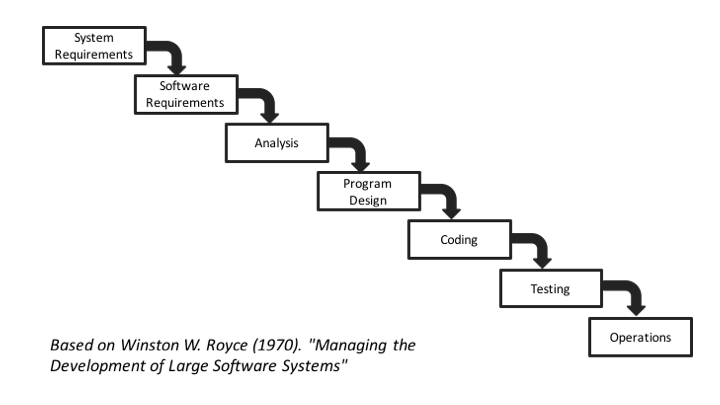

Before the advent of Agile approaches to software development there was waterfall. Idea of a waterfall approach was that the way to deliver a successful project was to write down in a requirements document absolutely all the requirements for the project. When that was done (let’s not worry too much right now how we’d know when it was done), that document would be used to create a complete system design. And when that was done (never mind about how we’d know when it was done), development would start. When development was finished, testing would start, and then when testing was finished, in theory, user acceptance testing would start.

That was the theory, but usually, at some point during either development (which would take far, far, too long - much longer than “estimated”), or during testing (which would reveal either that the system didn’t do what the customer asked for in the requirements, or, more likely that the system did do what was in the requirements, which it was now obvious to the customers, wasn’t what they now wanted) there would be a crisis.

Writing about it now, in the 21st century, it seems impossible to believe that this would be a reasonable approach to developing software. Indeed, it does sound impossible if it weren’t for the fact that at least on two occasions in the last six months it’s been suggested to me that this approach would work better than an Agile approach, or that we should revert to a waterfall approach because an Agile approach isn’t working.

Why is such an approach so appealing? I think a substantial part of the reason is the powerful appeal of “all”.

Same

“Real life Fagin ran gang of pickpockets from Hackney flat”

“Real life ‘Pretty Woman’ married her millionaire client in fairy tale ceremony”

Every now and then there is a story in the news of something that has happened in real life that is sort of like something that happened in a novel or a film. If we stop for just a second, we might ask why? Why would this be news? And lots of things happen in the world. The two described above, although unusual aren’t that unusual. Why should it be of interest to anyone that these turns of events match on a very superficial level? One answer is that, similar to the power of “all”, in its persuasive and attractive power of “same.”

These stories are interesting, and somehow rewarding because they show similarities between the world of imagination and the world of reality. In the world of waterfall projects, one powerful idea of success of a project was a project that was delivered exactly what was in the specification, exactly on time and exactly to budget: same specification, same duration and same cost equals success. Doesn’t it?

Same is very powerful in several other ways. Same is especially powerful when projects get started. How many iPhone apps, or Facebook apps were created with an argument of the form “everyone else is getting an app”. As noted by Robert Cialdini in his book “Influence”, “We view a behaviour as more correct in a given situation to the degree that we see others performing it.”

Always, Now and Forever

The past comes before present, the present comes before the past. Time isn’t symmetrical, it is fundamentally asymmetrical. So it’s not surprising that symmetrical thinking about time is very strange.

The Absence of Negation

As described above in the example of the “Number 3” in the peg board. The negation of specific idea makes that idea very real in a way that is very different from the actual logical implications of something not existing. “Not Number 3” logically means “anything but an elephant”.

Version - 0.1 - Aristotle

Delivering the Impossible [Working title]

Chapter 2

What is Agile?

One of the strange things about social media is that sometimes talk about work and talk with friends gets mixed up. As a result, friends of mine who know nothing of software development get to see me ranting about Agile or SAFE or someone behaving badly in a stand-up. Occasionally they mention to me that they have no idea what I’m talking about.

And some of these friends have actually started to read this book. As one put it “I read all the way through to the elephant.” And I’m wondering if it’s possible to keep those people reading through what has to be the next chapter of the book. This is a chapter which explains why these observations about “some” and “all” should be of interest to anyone who’s involved in managing projects, but especially software development projects.

To explain this, we need to talk about the Agile manifesto, and how it encourages a “some” approach to thinking about software development and then we need to talk about the most successful Agile method: Scrum.

But in order to explain what the Agile manifesto is, we need to explain what Agile is. And in order to explain what Agile is? Well, really to explain what Agile is, we need to explain what Agile isn’t and how we used to do things before Agile. Fortunately, all of this backing up to get a better run at things is totally relevant to the central idea of this book: that things go wrong when you use “all” where you should use “some” and things get better when you use “some” instead of all.

What is Waterfall?

Until the end of the 21st century it was widely thought that the best way to manage software development was to treat it like the engineering of complex physical structures, like engines or suspension bridges. This type of approach is often called a “Waterfall” approach because of the way that’s represented in diagrammatic form.

When a piece of software was required, it was understood that the best way to make sure that that piece of software was delivered “on time” and “to budget” was to make a list of absolutely everything (all of the things) that the piece of software needed to do in a “requirements document”. When that document was complete, and only when it was complete, another document would be written which explained exactly how those requirements would be satisfied. This would probably be called a “design document.”

Eventually, when the design was complete, some software developers could start to write some software.

When the developers had finished doing this, everything that they had written would be passed on to testers who would test what the developers had done against the initial requirements document. When they had confirmed that the software did everything that was outlined in the initial requirements document, the software would be handed to the customers to do their own testing, sometimes called “factory gate” testing, sometimes called “acceptance testing”. When the customers had convinced themselves that the software did exactly what they’d asked for in the requirements document, the software would be released and put live. And everybody would live happily every after. At least that was the theory.

What’s Good About Waterfall?

One of the things that’s good about the waterfall approach is its universal, intuitive appeal. Given the discussions that we had in the introduction and Chapter 1, it might be possible to see why.

The idea of doing all of something has tremendous appeal.

When you’re tackling a big, complicated project, making a list of everything (all the things) that you want the project to do seems like a good idea. It seems like the safest way of making sure that you don’t miss anything, that you get all the things that you want.

The other good thing about waterfall approaches to projects is directly related to this powerful, intuitive appeal. Put very simply, senior management like the sound of “all”. “All” sounds complete. “Some” sounds messy. Lots of projects like this got funded. And as the architectural writer Stuart Brand points out: “Form follows funding.”

What’s Bad About Waterfall?

So what’s wrong with waterfall? When I started in software development, “waterfall” project management wasn’t called “waterfall”:it was just called “project management”. It was simply the only kind of project management that there was.

The first two projects (an accounting system for an oil company and a weapons simulation system) that I worked on had been through extensive requirements gathering phases. They’d then been through complex design phases, and then, after a long, long time, software development had started. Both were multi-million pound development projects. And after the requirements, design, development and testing phases, both projects had had an unexpected, additional phase: litigation. Yes, that’s right. On both projects, the clienti had threatened to sue us as suppliers because they were so unhappy with the way that the work was going.

What brought on these crises? Several things. First of all, getting to the point where the customers could see working software had taken far, far, longer than had been initially estimated. This caused all kinds of our problems for our customers who were betting on the systems being available so they could build service stations, train personnel, start wars.

Secondly, when they customers did get to see the software, it wasn’t what they were expecting.The realisation that the software was not only late, but also the wrong thing caused a crisis in the clients so profound that they wanted us as suppliers to really smart. Blame, shame, wounding costs and reparations needed to be handed off onto the people who’d committed this abomination and so the lawyers were called.

Finally, by the time our customers got to see the software the world had changed. New territories with new requirements had opened up for the oil. Wars in different parts of the world looked like opportunities for the arms manufacturers. While we’d been beavering away writing the requirements, coming up with the design, writing the software and then finally testing it, the world had changed. A substantial part of why the customers didn’t want to pay for software we showed them, and so had called in the lawyers, is that even it was exactly what they’d asked for in the requirements document, it wasn’t what they wanted anymore.

But here’s an interesting thing. Both projects, when I worked on them were making money for the company. Both projects were also delivering software to the customers. In both cases the company had called in a negotiator who specialised in helping out projects that had reached this crisis phases. He was a tiny Glaswegian (I’m 5’ 5” and he was a good head shorter than me) called Terry.

Terry would negotiate with the clients; he would tolerate the their shouting and cursing and recriminations with good grace; he would find out which bit of the software the clients desperately needed most and he would agree to deliver that in a short space of time, say a month or so.

But part of that agreement would be getting the client to agree to drop the threats of the law suit and pay a little bit more money. Slowly but surely, the client would start to get a system that they could use and were happy with, if still not ecstatic. Slowly but surely they would forget the threat of legal action and concentrate on identifying what the next thing was that they wanted us to work on.

I didn’t really understand it then, but to me now, it’s obvious what Terry was doing. In the midst of customer wailing, gnashing of teeth and threats of legal action, Terry was negotiating the replacement of “All” with “Some”. Rather than promising “All” of the project, he was agreeing to supply “Some”. And this became much easier at the point where the client was really seriously looking at the possibility of ending up with nothing but a long and drawn-out law suit. Focusing on some rather than all also provided an opportunity to incorporate any changes that the customer wanted that weren’t in the original specification.

The Need for “Lightweight” Methods

Terry was, in this aspect a bit ahead of his time. But not that far ahead. By the mid-nineteen-nineties, several forces were combining in the world of software to make this kind of approach more principled and explicit. For one thing computers were getting all GUI - that’s an acronym for Graphical User Interface. Firstly widely available with the Apple MacIntosh, but then far more widely spread with Windows 95, users were wanting to point and click at things in windows and buttons and menus rather than type special commands into computer that had a very old-fashioned looking green screen.

And it turned out that GUI’s were really, really hard to specify in requirements documents. They were much better served by a process that “iterated” through a series of “prototypes.” That is, you start off with a rough sketch of what you want the GUI to look like and show it to the people who want it - maybe even give them a chance to try it out, you take their comments into consideration: “Where the hell’s the undo button?” “I thought this would be purple!” and then you produce another version. Each of those version is a new prototype. Each journey around the loop, getting feedback, making modifications and then producing a new version is an iteration.

ean while, in the USA, a change was being negotiated to the rules governing the use of an obscure computer network used by academics and military personnel and nerds. The rule change would allow the network to be used by commercial enterprises. And in Switzerland a researcher at the European Centre for Nuclear Research was making his idea for how to get access to documents on other people’s computers free to anyone who cared to use it. The internet and the worldwide web were about to meet and start to have children. Commentators were about to start using the phrase “internet speeds” to talk about the ferocious pace of change. And all of a sudden, nobody wanted to wait eighteen months to find out their software wasn’t what they expected and call their lawyers.

Still, it took a while: throughout the 90’s and into the 00’, various attempts were made to codify this new iterative, prototyping approach. These new methods, Rapid Application Development, Extreme Programming came to be generally referred to as “lightweight” methodologies. Although few people were happy with that as a label.

So in 2003 a bunch of these men who were interested in these “lightweight” methodologies (they were ALL men) got together in a ski lodge hotel in Utah to discuss a better way of presenting what they were doing. The result of that meeting was a 93 word statement known as the Agile manifesto.

Version - 0.1 - Aristotle

Chapter 3

Some and All in the Agile Manifesto

We will glorify war - the world’s only hygiene - militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti - The Futurist Manifesto

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it.

Through this work we have come to value:

-

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

-

Working software over comprehensive documentation

-

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

-

Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more.

The Manifesto for Agile Software Development

The Agile Manifesto

As we can see from the brief quotation of the Futurist manifesto, some manifestos state a position strongly and powerfully. They are a statement of strongly held beliefs and ideas. They are a call to action.

But the Agile manifesto starts out like this:

We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it.

Compared to many other manifestos, the Agile manifesto seems unsure of itself. Notice the ways that are being uncovered are not necessarily the best ways. They are merely better ways. They aren’t even completely known, they are being discovered. In its very first line the Agile manifesto emphasises the importance of some rather than all.

The Agile manifesto then moves on to talk about four things that its signatories have “come to value,” all of which are worth looking at in detail.

“individuals and interactions over processes and tools”

This is a doubly uncertain statement. It says that individuals and interactions are to be valued over processes and tools. Note that it doesn’t say that there’s no value in processes and tools. It also puts forward the idea of software development as an ongoing conversation rather than something that can be captured completely in a document.

But what this means for software development is only really clear if it is set against the background of the waterfall thinking which was prevalent at the time and which we talked about in Chapter 2.

If something is open to discussion, it is not finalised, it is not complete and the entire appeal of a waterfall approach relies on completeness.

If software development is an ongoing conversation, then the whole way that we approach it is going to have to change because the old approach of waterfall relies on the notion of the conversation being able to stop, for it to be possible for a stage in the process to be regarded as complete, conversation over.

“working software over comprehensive documentation”

This is worded gently but, in its own way, it’s dynamite. This is not an absolute statement (get something working rather than documenting everything). But there is something absolute about the idea of working software, and the Agile manifesto values it.

For the people deeply involved in the development and testing of software what exactly constitutes working software might be a lively debate. But on a more basic level, working software is an absolute requirement. There’s a piece of software, somewhere on some machine that will either run and do something, or it won’t. It either works or it doesn’t.

The process of getting anything to work at all is threatening to a project and its sponsors for one reason: when you try to get something to work, especially in software development, there’s a chance you might not succeed. What if the very first bit of a project that you try to get working doesn’t work? What does that mean for the big idea of the whole project? What would that mean for your reputation?

Trying to get something working and failing is a dangerous business. In fact the only thing that’s potentially more dangerous to a project is, well, getting something working. Why on earth would getting some software to work be threatening? Maybe now it’s time for another story.

I was working on a fraud detection project for a big retail bank. I was supposed to be the “Agile Coach”. But all the time that I’d been working on it, it had been a good, old-fashioned waterfall project. Often, trying to earn my keep as an Agile coach, I suggested that the best thing to do would be to start doing some actual development: “Working software over detailed documentation.” But I was told that that could only be done when the project was sufficiently detailed it could be estimated within “plus or minus ten percent.” When I asked what we needed to do to satisfy ourselves that we’d reached this level of certainty, I found that whoever I was talking to suddenly remembered that they had a dental appointment, or that they needed to rush off and pick up their kids from school. Even the ones that I knew didn’t have any kids.

Then, suddenly, requirements gathering stopped. Not because everybody was now certain how much development would cost within the fabled plus or minus ten percent, but for a far more powerful reason. The budget for analysis ran out.

And so, with the budget for analysis exhausted, the team started to do development in an Agile and iterative fashion, using an Agile method called Scrum (we’ll talk about Scrum a lot more in the next chapter). We planned just a fortnight’s worth of work at a planning meeting. Not all of the work. Just some. The development team worked on it for a fortnight. Every morning we had a stand-up meeting where we talked about the work that we’d done the day before and the work that we were going to do. Again, not even all of the work for the fortnight, just the small part that we were currently working on.

At the end of the two weeks we had a “Show and Tell” where we demonstrated this small bit of working software that we’d done to the people who represented the customer, the product owners (in Scrum there’s only supposed to be one product owner, but this was a far from perfect Scrum set up, so there were three); the stakeholders who’d instigated the project and the users inside the bank who would actually use the software when it was finished.

Fraud detection is a really important function in a retail bank. There were lots of stakeholders interested in seeing how the project was coming along. The Show and Tell wasn’t just a packed meeting room, but also people dialling in and sharing the presentation screen: in India where some of the development was happening; in Scotland; Northern Ireland; and in the South East of England where people who worked with the current system really wanted to know what the new one would look like.

One of the product owners talked through the working software showing very first screen of the new fraud detection system. And in the room and online, on what had been a very noisy conference call, there was a very awkward silence.

“I thought we’d agreed that the workflow would be organised by account holder rather than account number,” somebody said eventually.

I was in the room with the lead business analyst (BA). She frowned “No, I don’t remember that being agreed anywhere.” On the conference call there were gasps, sighs and sharp intakes of breath. “See the problem is…” continued the same voice “…fraud detection only really makes sense to us if we can look at all of the accounts held by one individual, rather than just looking at one account.”

Up to this point, millions had been spent on business analysis for this project. Months, if not years, of time, had been spent on it. And remember, so much of that time and money was spent in the hope of getting a complete specification, a specification that captured all of the requirements “within plus or minus ten percent.” Although nobody who could plausibly claim to have either teeth or children would ever admit to knowing what that meant.

But after less than ten minutes of letting the people who would actually use it look at the working software, it became obvious that a lot of that work would either need to be redone, or thrown away entirely.

This is what makes the Agile manifesto’s emphasis on working software so powerful, but it’s also what makes it so threatening and dangerous. No manager, no stakeholder, wants to find out that they’ve spent huge amounts of time and money on the wrong thing.

“customer collaboration over contract negotiation”

Again this value emphasises the incomplete, partial and conversational nature of software development. Just as there is no requirements document that can capture all the details. There is no contract that can capture all of the eventualities and guarantee, either valuable software for the client, or a reasonable margin for the developers. The whole process needs to be a continuing collaboration.

But remember, this isn’t to say that software development projects don’t need contracts. Looking carefully at what the manifesto actually says. It says that it values customer collaboration over contract negotiation. People react to this line in the manifesto in some strange ways. In fact what they do is to react to the suggestion of partial solutions absolutely.

For example, one way that people react is to say “There’s no way that we can do business without a contract.” This is to hear the idea that’s suggested in the manifesto - “contracts aren’t everything” and interpret absolutely as “there should be no contracts.”

Another way that people react to the suggestion of an Agile approach is to say “OK, you need to tell me exactly what an Agile contract will look like that will absolutely ensure that this project will be a success.” Yes, this is crazy, but variations of this demand are quite common.

Let’s think about what’s being asked for here. In response to the suggestion that customer collaboration should be valued more than contract negotiation, some one has said “OK, but I’d like you to tell me what the contract looks like that guarantees the success of this kind of approach.”

Could a contract be written that allows for every eventuality? Is it worth trying to capture every eventuality? Is the time spent on the “development team fall victim to alien abduction” clause worth the effort. As with the story I told above about the fraud detection project, how would you know when you were finished, even if you allowed yourself the margin of “plus or minus ten percent.”

But none of this really addresses the real reason that it’s not worth the time to try to get a perfectly-crafted contract and a minutely detailed specification. The real reason that either of those is a waste of time is because the situation that you’re drafting a contract for isn’t the situation you’ll find yourself in and the specification of what you think you want now isn’t anywhere near what you’ll ending up want. Or what you’ll finally get. Why? Because things change.

“responding to change over following a plan”

Let’s go back to that story of the fraud detection project and the awkward conversation that happened just a few minutes after looking at some working software. The way I told it, and the way it played out, was that people who currently did fraud detection, the people who were going to use it, had known all along that the system would only make sense if transactions were grouped by individuals rather than by account. But what if that wasn’t true?

What if the users had started to realise that this was a really important requirement once they’d seen the screens? What if their understanding of what they wanted had changed as a result of them thinking about what they wanted, or as a result of looking at what they’d asked for.

Highlighting that responding to change is the business that we’re in, rather than delivering on a plan attacks the whole idea of a project as being merely a missing peg on the peg board.

When we think of project management of software as the management of change it becomes more obvious that the empty slot in the peg board could indicate anything but 3 rather than just a 3-shaped whole that still just happens to need to be filled.

anagement of software development isn’t just a delivery of something that fits in a slot, it’s an exploration of what might fit in the slot. And as with any exploration, as we explore, our understanding changes.

The Power of Mildly Suggesting “Some”

The Agile manifesto gets its power from almost doing the opposite of what’s expected of a manifesto. It gently suggests that to some degree we try to do some of some things, that we do partial things partially rather than complete things totally. Taking these suggestions seriously, for example, by looking getting some working software as early as possible in a project, has powerful implications for how software development gets done.

By doing this, the Agile starts to give us an idea, possible a very counterintuitive idea, of how we might go about delivering the promise of this book - the impossible.

What the Agile manifest doesn’t do, and how could it in so few words, is give any good ideas about what we might do to make this actually happen in software development.

For that we need a method that essentially tells us that we need to keep doing some all of the time. And by far the most successful approach to that is a method called Scrum which we’ll deal with in the next chapter.

Version - 0.1 - Aristotle

Chapter 4

Scrum is About Some (but Also About All)

The Agile manifesto is gentle in its suggestions that we should think about some rather than all. Even so, the impact of those suggestions is powerful and the method that has allowed development teams to implement the ideas in the Agile manifesto most widely and effectively is Scrum.

Scrum is more direct than the Agile manifesto. Scrum recommends four meetings: the daily Scrum or stand-up meeting; the planning meeting; the show and tell; and the retrospective. Scrum also recommends three roles for the team: Scrum Master; product owner; and team member.

Beyond that, Scrum just requires just a couple more things: that the work going to be done by the team is collected in a list called the product backlog; and that the team should be between 5 and 9 people. Teams bigger than that, should be broken down into multiple teams that are about that size.

Daily Scrum or Stand-up

The most obvious and noticeable thing about Scrum is the daily stand-up meeting or daily Scrum. This is the aspect of Agile that people who are only tangentially connected with Scrum teams notice and remember because it is different from normal office behaviour.

The meeting is called a stand-up because it is held standing up, less comfortable than sitting down, and so less likely to run on. In cases where a team is distributed across several locations, it is generally still a good idea for the members of the team that are in an office to stand up.

The daily Scrum is a powerful way of bringing “some” into the software development process. Each of the members of the development team are asked only to answer the following questions:

- What did I do yesterday (the last working day)?

- What am I going to do today?

- What is blocking me from doing what I want to do?

The Scrum/stand-up meeting leads the development team to focus on what is happening right now and in the very immediate future. A meeting that is supposed to be narrowly focused is vulnerable to that focus being lost. When a team member mentions that she is having problems getting access to a particular database system, it’s natural for other team members to try, in the stand-up meeting, to suggest possible solutions to her problem. It’s the job of the Scrum Master to try to keep the stand-up on track by suggesting that anyone who thinks they can help can talk to her immediately after the stand-up.

Similarly: if there are big political events going on in the world; if someone’s cat is ill; if someone’s national football or ice hockey or rugby team have won something; it’s likely that people might want to chat and joke about that rather than talk about work. Again it’s the job of the Scrum Master to try, as gently as possible, to manoeuvre the conversation back to answering the three questions.

Moving Together in Time

The stand-up is a physical act, not just a psychological one. Another requirement of the daily Scrum is that it happens every working day in the same place at the same time. A slightly unusual, formalised, physical movement, done at the same time, in the same place every day, with quite strict rules as to how it should be conducted? Without pushing the analogy too far, it’s possible to see that the daily stand-up is a bit like a religious ritual, or military ceremony: like roll call; morning prayer; or a march around the parade ground.

So the daily stand-up is a slightly unusual physical act which aids a slightly unusual, for project management, psychological act: that of focusing on what is happening right now, rather than on the whole of the project. Even so, this brief, change in behaviour and thinking might be the most important and powerful aspect of Scrum.

Backlog Prioritisation

In sprint planning, which we’ll talk about in a minute, the product owner, the product backlog and the development team come together to achieve a shift in focus from the “all” of traditional Waterfall planning to the “some” of Agile planning.

As we mentioned above, the product backlog is a list of the things that need to be done on a project. It might be tempting to think that this is very similar to the requirements and specifications documents that are written in a traditional waterfall project. But the product backlog is different from a traditional specification document in at least three ways.

The Product Backlog is Divided into Bits.

The product backlog differs from a traditional requirements document in that it is a collection of pieces rather than a single whole. These bits that are collected together in the product backlog are referred to as “stories”. We don’t have to worry just now about the precise details of what constitutes a story. What’s important is that the backlog is a collection of individual items rather than a single, monolithic document. This allows the second major difference from a specification document: deliberate vagueness and incompleteness.

The Product Backlog is Deliberately Vague

Not everything in the product backlog has to be fully detailed. Items which are currently a low priority can have almost no detail at all, they can also be left in big chunks. Conversely items that have been give top priority, do need a substantial amount of detail in them and do need to be broken down into smaller bits.

That items in the product backlog which are not top priority don’t need to be completely detailed makes the product backlog more useful than a traditional specification. Even the items at the top of the backlog, those with the highest priority, don’t need to be fully and completely detailed. This is useful because it stops stories getting held up simply on the grounds that they aren’t “complete”. What Scrum is explicitly admitting is that further work and discussion will need to go on about requirements when those stories are being worked on by the development team.

The Product Backlog can be Prioritised and Re-prioritised

One of the main reasons that the product backlog is collected in bits is so that they can be ordered in different ways. This is one of the main jobs of the product owner: to prioritise the items in the product backlog.

By doing this the product owner becomes the role in Scrum which conjures most powerfully with “some” and “all”. All of the work that might be done on a Scrum development project is kept in the product backlog. But one of the most powerful aspects of Scrum is that at the beginning of every sprint the product owner needs to decide on some of these things that should be planned to be worked on by the development team.

ost product owners find this extremely difficult, at least at first. Looking at things from the point of view of symmetry and asymmetry we get an idea of why. The act of prioritising what needs to be done is “all destroying.” Once we break ground on a project and actually start to do it, there’s a strong possibility that we will find problems with the vision. Once we start to do a project, there’s a strong possibility that we will realise that the whole of the project could take much longer than was initially predicted.

Again, it is often the Scrum Master who is left with the job of persuading the product owner to articulate which items should be a priority.

Help with Prioritisation

One strange thing about this resistance to the prioritisation of the product backlog is that often people know which bits of the product backlog are the most important and should be the priority.

I worked on a fraud detection project that was estimated to take nearly two years. Even so, the bit that everyone knew was most important was an algorithm that detected false positive indications of fraud. This was perhaps only five percent of the whole project and could have been delivered in just a few months.

It can be useful to ask the product owner which small part of the project it is that everyone knows should be done first. Or having talked to other people who know about the project, the Scrum Master might suggest this as the bit that should be given highest priority.

Another way to help the product owner is to explain that even though everything in the product backlog may need doing, the development team can’t do all of the things in the product backlog at the same time. So the question of prioritisation then becomes a slightly easier question: even if we agree that we’re going to everything in the product backlog, where should we start?

Once the team has started, there’s then an obvious, easier follow-up question than explicitly pushing for prioritisation: what should we do next?

Backlog Refinement

Scrum mentions just four meetings, but often there is an extra meeting which is held once or twice during each sprint. This is a meeting where the product owner talks through with the team what is coming up next.

The aim of these sessions is to make the stories a bit more detailed. Detailed enough that they’re ready for development. But there’s a symmetrical danger here, a danger of looking for all rather than some of the detail. Teams have to get the hang of knowing when a story is detailed enough that it can be planned, otherwise they get stuck. Again, part of job of the Scrum Master is to spot when the team are getting too hung up on detail, or decide that a story has enough detail and move on to discuss something else.

Complexity Estimation

In Agile and especially in Scrum, rather than trying to get an exact idea of how long things are going to take, we try to get a rough idea using complexity estimation. This is done by estimating how complex a story is relative to other stories: if a story is the same complexity as another story we give it the same complexity score. If it’s more complex we give it a higher complexity score and so on.

This means that when we get to the end of a sprint we will have a list of stories that we’ve finished and a count of complexity points. This gives us a rough idea of how many complexity points we could manage in the next sprint.

Sprint Planning

If the product owner has managed to prioritise the backlog and some refinement has been done on these stories, sprint planning should be a fairly painless exercise.

The team and the product owner go through the stories which are top of the product backlog, discuss them and plan them in priority order until all are agreed that they have planned enough work for the next sprint (sprints are typically two weeks long).

Note that this is an agreement between the team and the product owner. The product owner isn’t telling the team what to do. The team and the product owner are agreeing what to do. How do the team know how much work will be enough for a sprint? The team uses how much work was done in the previous sprint, estimated in complexity points, as a guide.

Again, the role of the Scrum Master is to spot when either the team have taken on too much; when the product owner is pushing the team to take on too much; or when there is still some room to plan more.

Review, Show and Tell, Showcase or Sprint Demo

Scrum dictates that at the end of every sprint there should be a meeting where the team demonstrate what they have done in that sprint. For some reason no one seems to have settled on name for it, it’s called either the “Sprint Review”, “Show and Tell,” or the “Showcase” or the “Sprint Demo.” Of all of these names, “Show and Tell” appeals to me most, so it’s the one I’ll use.

y own experience is that the “Show and Tell” can be one of the most difficult meetings in Scrum and the reason is because of this relationship between “some” and “all.” In the show and tell, the people who are paying for the project get to see what they’re getting for their money. Certainly in the early days of a project, this isn’t much.

The people who are looking at this “working software” are the people who have bought into this project because of some dream: some big, simplified, easy to state and attractive “all”. Sometimes being faced with the gap between what has been promised and what needs to be delivered, is difficult.

That is possibly why getting the people who need to come to the showcase: senior stakeholders and even the product owner can be hard. A lot of the time they won’t like what they see, or they won’t feel that what they see is near enough being a finished product to be worth their attention. Often, like the joke about the elderly ladies complaining about their stay in a hotel, not only is the food terrible, it’s in such small portions.

Again it often falls to the Scrum Master to ensure the continuing engagement between the development team and the stakeholders - offering some explanation of what the Product Owner is actually looking at and also explaining to stakeholders what the value is of some small piece of working software.

The Perfect Product Owner

So what should stakeholders do in these circumstances? For a long time, I thought what they should do is come to all the meetings and take the extremely slow progress on the chin, give detailed and definitive feedback and most of all keep their nerve.

Since, then I’ve started to reflect on the product owners I’ve seen who’ve really worked well, and they don’t do that. There are two modes of product owner that I’ve seen really work: stealth and what I’m going to describe as “anti-Pharaohs on elastic.” (OK, this needs a better name).

Stealth Product Owner

On a project where are there are lots of big beasts (i.e. important stakeholders that can’t be argued with) the product owner provides good solid guidance about priority and good feedback to the team on what they are producing, but never confronts the big beasts. This means that the shiny “all” goal and dream of the project and the unreality of deadlines is never challenged, nor some of the fundamental obstacles to the product’s success are never addressed or removed. Still when the big beasts aren’t around, the product owner does what they can. This isn’t a perfect arrangement, but it can work and indeed can be the only possible solution where product owner is too junior to stand up to the big beasts, or in an environment where any discussion of the real state of the project is likely to result in dismissal.

Anti-Pharaohs on Elastic

The Pharoah in book of Exodus in the Bible asked the children of Israel to make bricks without straw. Pharaoh wasn’t an idiot, he knew what he was doing, he knew that making bricks without straw was impossible and he did it as a punishment.

Unfortunately, the Pharaohs that we encounter on modern projects often don’t know that they’re asking for the impossible. They ask for software that talks to a database that doesn’t exist; they ask for software using a technology that doesn’t work properly yet; or they ask for something, but totally refuse to give the requisite detail of what it is that they want.

One of the things that Scrum does is that it acts as a way of testing hypotheses, of trying out ideas like “We can connect to this database” or “this cool new technology actually works” and we’ll talk about this in the next chapter.

By breaking the work up in to small chunks and trying to do those chunks in a short space of time it soon becomes obvious what the problems are with a project. And quite a few of these problems are “bricks without straw” problems. They are problems that if they aren’t solved will mean that the project has no chance of success.

A good product owner behaves in ways that might seem contradictory, they behave in an “elasticated” fashion. When things are going badly, they keep themselves at a slight distance from the project. But they also pay attention to the demands of the team for help with their bricks-without-straw problems. They stay sufficiently in-touch that if and when the project does start to succeed, they can snap back and be much more involved. When it comes to taking the credit, they are of course front and centre stage.

A Good Product Owner has a “Some” rather than an “All” attitude

So, although the stealth product owner and the elasticated non-Pharoah product owner might seem to be behaving very differently, their attitude to the product is quiet similar. One way that you might talk about the successful approaches of both the stealth product owner and the elasticated product owner is that they aren’t fully invested in the project. Another way of saying this is that this isn’t an “ego” project. This kind of language highlights two all ways of looking at a project which are extremely damaging.

“Fully invested” suggest that someone has put all of their resources into this single project, possibly they have also put the full weight of their reputation behind a project. Given the chances of success of any software project, putting your whole reputation behind a project probably isn’t that smart a move.

An “ego project” (“ego” is the Latin for “I”) is a project that someone is directly and closely associated with. Again, this isn’t a sane way of thinking about software projects because even with well-specified, well-managed software projects, there is still a large amount of uncertainty and a chance that they will go wrong. What’s important to highlight here is that associating the ego with a project is symmetrical thinking. It’s thinking that associates success with there being a symmetry between what’s in the mind of the product owner and the software that’s produced. In very bad cases, this can also mean taking any bricks-without-straw problems that are identified in the project as personal criticisms.

The best product owners don’t do this. They have some attachment to the project (especially when it’s going well) but they do not identify with it completely and they help wherever they can to remove “bricks without straw” problems.

Retrospective

The retrospective is a short meeting where the team get together and discuss what went well; what didn’t go so well; and what they might do differently to improve the performance of the team.

The retrospective also enforces a some perspective because, although there might be discussion of what an ideal situation would look like, one of the main purposes of the retro is to identify specific next actions to improve the way that the team is working.

For product owners who aren’t Pharoah (i.e. they’re interesting in giving their workers the tools they need to do the job) the retrospective is also full of vital information because it gives a list of the problems that are stopping the team from doing their work.

I’ve been facilitating retrospectives now for about 8 years and from the very beginning I instinctively felt that, although it was a good idea to capture all the points that arose at the retro, it was also a good idea to boil those points down to just two or three points which would get reported more widely: just some of the issues.

If this effort isn’t made, the retrospective can easily fall prey to unhelpful “all” thinking. For instance there can be the idea that all of the actions that come out of a retrospective should be completed before the next retrospective. This can be made even worse by making each action a commitment (we’ll talk about commitment and consistency in a separate chapter).

It took me quite a while to realise that the natural cadence of resolution for actions from retrospectives isn’t the same as the cadence of Scrum sprints (which are typically every two weeks). Some issues that come out of retrospectives can be fixed quickly, some will take longer, some will be problems throughout the lifetime of a project.

Scrum and “All”

In this chapter we’ve explored the way that Scrum is about “some”. In particular the meetings that Scrum recommends are a way of forcing the product owner and, by extension other stakeholders to think about the detail of some rather than the general idea of all.

But Scrum isn’t just about “some”. Scrum is also about “all”. One way that Scrum is about “all” is that it is absolute in its partiality. For example there is the insistence that the Scrum happens every working day at the same time, in the same place and that no other questions are answered other than “what did I do yesterday”; “what am I going to do today”; “what’s blocking me?”.

Scrum also focuses on completeness. The aim of the Sprint is to complete all the work that was planned in the Sprint and that work is not counted as being “Done” until the working software has passed its tests and it has been accepted by the product owner.

A substantial part of the power of Scrum is in its approach to attacking symmetrical thinking and replacing it with asymmetrical, rational, logical thinking. But, Scrum being a human endeavour, it is in itself vulnerable to inappropriate and unhelpful symmetric thinking. Below are some of the ways in which Scrum can end up insisting on “all” where it would be better to think more carefully about “some”.

Fallacy No. 1: Scrum is a general framework that can be applied to anything

Scrum works very well for software development, where once work is started on a product backlog item, it usually can continue until the item is done. Scrum is less well-suited to managing other kinds of tasks.

I’ve been involved in many Agile coaching groups inside large organisations. To my shame, many of these groups have been seduced by the idea “we’re advocating Scrum to our clients, we should probably use it ourselves.” Very often this gets as far as planning in sprints, but it misses out some of the things that are really important about Scrum. For example, such attempts at using Scrum to manage consultancy-level work often remove,the main engine of some in a Scrum team - the daily stand-up. They sometimes also miss appointing either a Scrum Master or even a product owner and then wonder why nothing gets done.

Fallacy No. 2: All Stories can be broken down into smaller and smaller tasks

This is in direct contradiction to the idea that stories have to be just detailed “enough.” The reason that we don’t insist that they are completely (all) detailed is that this is impossible and the insistence stops the backlog refinement process dead in its tracks.

Sometimes, some breaking down of stories into more detailed tasks is useful. But insisting that all stories be broken down into the smallest level of detail brings us back to the waterfall problem of not knowing what the standard is for “completely detailed.”

The false idea that everything can be broken down into smaller and smaller tasks is also possibly an attempt to deny one of the most important truths about software development: it is knowledge work. It requires the solution of problems by smart people and quite how those problems will be solved isn’t something that can be broken down into discreet steps.

Fallacy No. 3: Everything that is planned in sprint planning should be completed at the end of the sprint

One of the “Scrum values” which is outlined in the admirably brief “Scrum Guide” is commitment. Commitment and consistency is a powerful psychological principle, which aligns well with “all-ness thinking” and “symmetry”. In the introduction, we’ve already seen how dumb this kind of thinking can be and it’s such a powerful way of behaving badly using symmetry that we’ll devote a later chapter to it.

From the point of view of “some” and “all” it’s interesting that if too much emphasis is placed on the idea of completion of everything that was planned for the sprint, “all”-ness can spread. The development team might begin to insist that stories that are committed to in planning are completely (“all”) detailed. When any vagueness or uncertainty is unearthed the team may down tools on the stories; mark them as blocked; and stop work on them until all uncertainty is removed. They might also disavow any committment to a story which they said they would do, but which then turned out to be “incomplete.”

Scrum Master

So what does the Scrum Master do? One way to think of the Scrum Master is that they are the keepers of the “some” perspective. The Scrum Master is in many ways the “some” master (oh dear). In the daily stand-up they try to keep the team focused on what happened yesterday, what’s happening today and anything that’s immediately stopping that from happening. They keep the focus on the small picture.

In planning and backlog refinement, they help the team and the product owner agree to take on some of the work from the product backlog. They also reassure the team and product owner that the work they take on does not need to be completely (all) detailed, but can be planned when it is detailed enough (some).

During the sprint, they help the team focus on getting some of the work done but here they also focus on the absolute requirement of Scrum to only count work as done when it has produced working software.

Conclusion

In this chapter I’ve looked at the ways that the Scrum method encourages, even forces a “some” perspective on the work that needs doing in software development. This focus on some is powerful for at least three reasons.

Something starts happening

The stasis and paralysis that can afflict projects that insist on all requirements being completely ready before they can proceed is avoided by the willingness of Scrum to start working on some of the requirements when they are good enough. This perhaps the most powerful aspect of Scrum.

Working Software

The focus on getting some of the work in the product backlog working produces working software which could potentially be valuable to the customer: providing customer feedback; clarifying in the customer’s mind what it really was they they wanted; and delivering revenue to the organisation.

A Better Idea of Obstacles

By trying to do some of the work in the product backlog, Scrum provides us very quickly with a far more informed idea of what obstacles there might be which could prevent us from doing what we want to do.

By doing this Scrum is also checking the vision and the dream of “all” of the items which constitute a project against the “some” of what has actually been achieved. In this way Scrum is a method for making explicit and testing the hypotheses about the project which are implicit in the work in the product backlog and it’s this hypothesis testing aspect of Scrum that we’ll look at in more detail in the next chapter.