Not Dead Yet - that's how they found him!

Not Yet Dead - That’s How they Found Him

There’s this story that James Thurber tells which I always think of when I’m trying to communicate anything. He’s a very young newspaper reporter and he is on the crime beat. He’s sent off to cover a murder and he comes back with a story that starts at the beginning - with neighbours hearing shots being fired, covers the police being called and ends with the body being found.

When he shows this to his editor, his editor says “No, no, no, you’ve just covered things in chronological order, you need to start with the most important thing that happened - that needs to be the first sentence of your story - the first word if possible.”

So Thurber goes away and rewrites it and his new piece starts “Dead! That’s how they found him….”

I know that’s where I have to get to, I have to get to a situation where the most interesting and valuable things that I’m trying to say hit you right between the eyes at the very beginning. But I’m not there yet, the truth be told, I’m a bit stuck, so rather than just sit around and do nothing, I thought I would tell the story in a semi chronological fashion and see if the actually structure will reveal itself.

So where we left it at the introduction was that I’d read a book called “Dead Man Working” and that had reminded me of a set of blog posts about work and the American version of “The Office” TV series - “The Gervais Principle.”

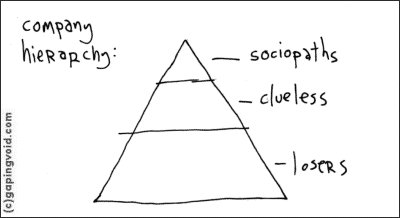

In this article by a blogger and now Author called Venkatesh Rao, there’s a discussion of this cartoon by Hugh MacLeod.

Although Rao’s analysis of The Office is really interesting, it was his commentary of this breakdown of the world of work into these three groups that made at least some of the scales drop from my eyes when I first read it, it seems now checking the dates, just after it was written in the Autumn of 2009. In some ways, these are obviously offensive names - and they’re names that in some ways I wish I didn’t have to work with. But let’s just run through, really quickly, what they mean.

++ The Clueless The clueless are the people in an organisation who, as the Americans would say, have been “drinking the Koolaid.” They think that the company has their own best interests at heart (or fear that it doesn’t). They are loyal to the company. They believe the myths about the good it does. They believe the “Big Brother” pronouncements that reassure then that they have always been at war with Oceania. Although it definitely sounds like it, this is not necessarily a totally negative designation, and the Clueless are not Clueless about everything.

In Shakespeare the “clueless” often turn up at points when tragedy strikes as honest and decent, and actually knowing right from wrong e.g. the poter in Macbeth.

++The Losers Losers are people in an organisation who are not getting the absolute most that they can out of their talent - they’re trading a safe, dull job for a regular pay check. Again, although this sounds very critical (this is really needed for the rhetorical force of the cartoon), this really refers to a group that is actually very talented.

The trouble of the losers is not that they’re not talented, but that they think their their talent will, and should save them. They are attached to their competence. This is a very important concept that I’m going to come back to again and again, because it is one of the most important ways in which the sociopaths manipulate the losers.

++The Sociopaths Again - these aren’t good names. The sociopaths are the ones who have either figured out through bitter experience, or were possible already borning knowing, that life isn’t fair. Loyalty to the company won’t save you, your talent - no matter how prodigious it is won’t save you. The only thing that can possibly save you is to understand that working in an organisation is a game, an amoral game. The way to win is to take the credit for the success of others and make sure that a cadre of loyal cluess and fuming losers take the blame for anything bad that comes along.

On the back of reading “Dead Man Working”, I recently went back and read Venkatesh Rao’s original post. In the intervening time he’s written a series of follow-up articles an I read those as well. And in one of them - I think it’s where he’s talking in more detail about the Losers, he mentions the concept of illegibility. Pointing out that’s what’s important for losers is that they maintain “illegibility” as to exactly how talented they are relative to the other losers in the group. And he mentions a book by James C. Scott called “Seeing Like A State”.

This notion of legibility and illegibility seemed to be me to be a really useful one when thinking about project management. Because it seemed to me that very often the currency in project management was fake legibility - clear plans, definite deadlines, precise estimates and also a general resistence to real legibility - actual problems, genuine limitations and real illegibility, uncertain risks, uncertain timescales.

And what came back to me while I was pondering this one morning was something that a friend who works in software development in merchant banking had said to me, again two maybe three years ago - about project management:

Sooner or later, someone has to lie…*